I can't believe it has been two weeks since my last post, but we did go down to the woods yesterday, the Virginia woods in the late-1700s where a force of British and Hessian troops sought to capture an American fort.

The scenario had a fore of eight British and eight Hessian regiments, plus a unit of light dragoons, plus supporting artillery, advancing through a heavily wooded terrain toward a fortified position at the far end of the table. The Americans needed to guard the central road and it crossroad to enable a vital supply column to make it to the fort.

The British (my command) took the left hand side of the table while the Hessians moved up the road. The Hessians had the harder task with just a narrow corridor to move through, whereas the British, once they cleared a narrow gap in the woods, were able to deploy on a wire front.

|

| The British cross the river and make for the gaps in the woods that lead to the clearing beyond. |

|

|

|

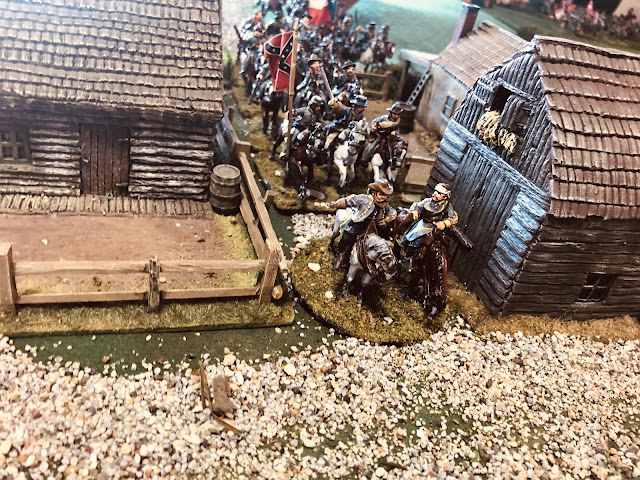

"Through there, sir!"

Without resistance the British made it to the clearing, brought up their guns and opened on the American militia, while the infantry deployed.

The British gunfire soon drive back two militia battalions and the British infantry surged forward.

But the Hessians struggled to get going up the narrow corridor.

The American brigade in front of the British rapidly disintegrated and the remnants fled back to the fort with the British in hot pursuit.

Along the road the Americans struck back and dispersed the British light battalion, but were thrown back by the British guns.

On the Hessian front things could have gone better. An attempt by one battalion to drive some riflemen from a wood did not go well and they were repulsed. When some lurking American cavalry charged the battalion was driven off. It took the Hessians some time to rearrange their lines.

The Germans met fierce resistance from two battalions of militia in a small redoubt, and were repulsed, much to their chargin.

Eventually the Germans cleared the redoubt and firmed a line along the cross road.

Meanwhile the Americans waited behind their fortifications

The British infantry in until now has suffered trifling losses. As they cleared woods they prepared to assault to the fortifications.

They quickly engaged the enemy in a fire fight, but it became obvious that they were not going to drive the American infantry from their trenches and the pulled back. The siege battery would be required to do its work before the American fortifications could be attacked.

Here the game ended in a glorious British victory.

Thanks to John L for most of the Hessian photos (I didn't get across that side of the table too much during the game to tame many).

|